Why take one rusty tool when you can take two? When I found that axe in the crate of rusty tools at the cruft swap, I took something else – a Coes wrench. These wrenches are extremely common. They were produced in various forms from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th. In the early 20th century, the factory was producing 3600 of them per day.

For around fifty years, this was what you would buy if you were looking for an adjustable wrench, but today they are almost forgotten. One recent reference I found was that it is one of the weapons available in Team Fortress 2.

First, Some History

The ancestry of this wrench can be traced back to English coach wrenches which existed in the 18th century. At this time, standard sizes of nuts and bolts did not exist, so a set of fixed size wrenches would have been useless. The simplest examples had a movable jaw set with a wedge. But in some, the shank of the wrench would be threaded, and the handle would turn, acting as the nut to move the jaw back and forth1. These had the disadvantage that they could not be adjusted with one hand, and could also be loosened accidentally while pulling on them, which would have been a very frustrating experience.

In other examples, the handle was fixed and the jaw included its own nut. The first US patent for a wrench of this type was 7254X, issued in 1832 to Henry King. Subsequent patents for improvements include 9030X issued in 1835 to Solyman Merrick of Springfield, MA. All of these wrenches still shared the disadvantage that they could not be adjusted with one hand.

The Coes family lived in a village called New Worcester, which was later to become a part of Worcester itself. They were farmers of Scottish origin. Loring Coes was born in 1812 and apprenticed as a carpenter before joining Kimball & Fuller, a manufacturer of woolen mill equipment. Aury was born in 1817, and went on to work at the same firm. In 1836, they bought out the company together and continued under the name L. & A. G. Coes. But in 1839 a fire in their building burned down their shop, and they were forced to take jobs as patternmakers at a foundry in Springfield, MA. As makers of wooden machinery parts they were skilled carpenters, and making wooden patterns for castings was a natural transition. They worked next door to the shop making the Merrick wrenches and this seems to have inspired them to improve on the design 2.

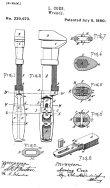

They filed the first patent for their wrench in 1841, distinguishing it from previous designs because it could be adjusted with one hand without changing one’s grip. The first Coes Wrench patent, 2054, issued in 1841, achieved this by mounting the jaw on a smooth shank and providing a separate screw turned by a knob adjacent to the handle. In the patent drawing below, they show their wrench next to the Merrick wrench to illustrate the difference in design:

By 1843, they were back in Worcester, producing these wrenches. Numerous patents hint at how they increased production from a few dozen wrenches per day in the 1860s to thousands per day in the 20th century. Three show different designs for dies to form the shank of the wrench. Another depicts a machine for producing a screw blank complete with knurled knob, ready to be threaded. Others still deal with the development of tooling to form the piece comprising the head and the shank of the wrench. The coolest patent I saw was 804706, granted to Loring in 1905, when he was 93. It shows a carousel-like contraption that allows for “continuous milling” of many wrench heads at once:

Finally, numerous patents tell the story of how the handle design progressed from the original patent to the most modern version. The chief difficulty seems to have been to seat the handle securely enough that the force of the lower jaw wouldn’t crush it or force it off the shank. There were two solutions to this: one, was to use a set of ferrules, like in patent 87547. The other was to thread the shank and use a locking nut to keep the handle on from the inside, e.g. patent 122108. The wooden handle was fragile, and would not stand up to hammering on the wrench handle to loosen a stuck nut. It was later replaced with a steel frame and wooden inserts – this was called the “knife handle wrench” and is the type of handle that my wrench has. There were several patents for this but the first was 229673. The Coes company later released a steel handled wrench that did not have any wood at all.

A brochure published sometime after Loring’s death shows three varieties of wrench, the steel handle, the knife handle, and a “hammer handle” that is shaped like the steel handle but has wood inserts. The brochure describes the components of each wrench in detail and talks about load tests and a 16-step inspection process. In 1895, the 6” knife handle wrench cost 50 cents (around $14.30 in today’s currency) 3.

The Coes Brothers also purchased a firm that manufactured blades for machinery, and built a separate factory for their production. Although the wooden handled wrench is called the “knife handle wrench,” they did not manufacture handheld knives – their knife factory only produced knives for machinery. A few patents deal with this also, one showing how to make a rolling mill to forge-weld a steel cutting edge onto an iron knife blade.

The brothers split up their operation in 1869, with Loring taking over the knife business and Aury building wrenches at a third factory site. It seems that Loring could not leave well enough alone because he built a new wrench factory and for a time, both of them were turning out “authentic” Coes wrenches, each one putting out advertisements claiming to be the true Coes. Aury met an untimely death in a carriage accident in 1875, at which point his sons took over. The two firms were recombined to form Coes Wrench Co. in 1888. Loring took sole ownership and renamed the company to Loring Coes & Co. Inc in 1902. The back-and-forth name changes and transfers of control make me wonder what Christmas dinners were like at the Coes household.

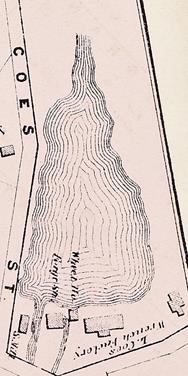

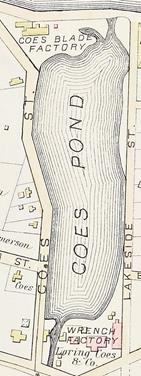

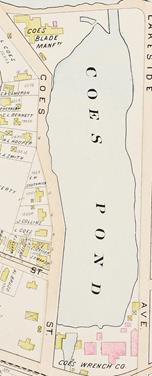

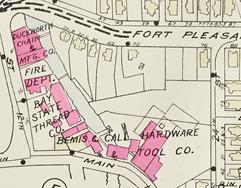

The two factories were located on opposite ends of Coes Pond. The wrench part of the business was located on Coes Sq. at the lower end of the pond, while the knife part of the business was located at the higher end, between Coes Pond and Coes Reservoir. A map from 1896 makes this distinction, but by 1911 both sites are labelled “Coes Wrench Co.”

Here are some maps of Coes pond through the years (Sources 18704, 18865, 18966, 19227):

While the Coes brothers moved back to Worcester, the wrench industry in Springfield continued, for example patent 23751 issued to A.D. Briggs in 1859 for also attempting to make an improvement on the Merrick wrench that could be adjusted with one hand. The Bemis & Call company in Springfield produced many types of wrenches including the Briggs wrench, pipe wrenches that functioned on the same principles, and combination pipe and machine wrenches.

Meanwhile, Loring died in 1906, working till the very end. Without its captain, the company stagnated. The development of standardized fasteners, standard wrenches and sockets, and the Crescent adjustable wrench (company founded in 1907) all contributed to the decline of the Coes brand. In his famous transatlantic flight across the Atlantic in 1927, Charles Lindbergh brought with him only a Crescent wrench and pliers for tools8. In 1928, Bemis & Call acquired the Coes Wrench line. Coes wrenches stamped “Springfield” were made after 1928 by Bemis & Call. My wrench is one of these.

In 1939, Bemis & Call was acquired by Billings & Spencer of Hartford, CT but for a time continued to make wrenches at the same location. Eventually their production was moved to Hartford, and the last Coes steel handle wrench appeared in a Billings & Spencer catalog in 1962, more than 120 years after the first Coes wrench was made. This was also the year that Billings & Spencer was acquired by Crescent Niagara, makers of the Crescent wrench 9.

Back in Worcester, the Coes knife business continued until 1991, when it closed due to the failure of a bank that had given them a loan. The knife factory stood abandoned for some time before being demolished.

The Factory Sites Today

I drove to upstate NY this summer and thought I’d swing by the original location of Bemis & Call (where my wrench was made) and the original Coes locations. The Bemis & Call factory site was easy to locate on a 1920 map of Springfield10.

The buildings are still there, occupied by various tenants. The website for the building refers to it as “The Monkey Wrench Building.”

The Coes factory sites have been completely cleared. A project document I found online says that the remains of the Coes Knife factory were demolished in 2005 to make way for the park at that location11.

The Coes Wrench factory site likewise has no obvious remains, except for a few pilings in the water.

Back To The Wrench

My first step with the wrench that I had was to de-rust it just like the axe. I went to the additional step of polishing it with a Dremel to give it a bit more shine. It really looks nice with that wooden handle.

I also took a few glamor shots on our welding table and on a Bridgeport knob:

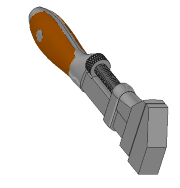

My neighbor at Artisans Asylum, Scott Janousek, has been doing some 3D scanning projects lately using his NextEngine 3D scanner, and he was kind enough to 3D scan my wrench. This produced the following result, which was quite rough:

I used SpaceClaim to create a 3D model of the wrench based on the scan – what’s called “reverse engineering.” First, I placed planes based on some selected mesh triangles to define the more angular features. For the handle and the lower jaw, I traced the cross-sections of these parts with curves, and lofted between them. I created this 3D model of the wrench (click to zoom and rotate):

Here it is as a STEP file.

This is the first time I’ve reverse engineered a design using a 3D scan. The 3D scan definitely saved a lot of time in modeling the curves of the handle, though it probably isn’t accurate to the millimeter.

The obvious last step was to 3D print a new Coes wrench using my model. I used the uPrint 3D printer that we have at Artisans Asylum. For $14.82 I had a working ¾-scale Coes wrench that bears a fairly strong resemblance to the original. I printed it in four parts, with the mating surfaces offset by 0.005”. It took a bit of sanding to get the jaw to slide smoothly and to get the screw to work.

Should you want to print this yourself, here are the STL files: 1 2 3 4.

-

A short history of Coes Wrench can be found here. A much more in-depth account can be found in a short book called The Brothers Coes and Their Legacy of Wrenches which clarifies a lot of confusing points and is my source for most of this article. It’s a self-published book that can be ordered here. ↩

-

Atlas of the city of Worcester, Worcester County, Massachusetts published by F.W. Beers & Co., 1870 p. 21 Source↩

-

Atlas of the city of Worcester, Massachusetts, published by G.M. Hopkins, 1886 p. 28 Source↩

-

Atlas of the city of Worcester, Massachusetts, published by L.J. Richards & Co., 1896 p. 19 Source↩

-

Richards Standard Atlas of the city of Worcester, Massachusetts, L.J. Richards & Co., 1922 p.20 Source↩

-

https://home.comcast.net/~alloy-artifacts/billings-spencer-company.html↩

-

Richards Standard Atlas of the City of Springfield and the Town of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, published by the Richards Map Company, 1920, p.11 Source↩

-

http://www.worcesterma.gov/uploads/db/ea/dbeaae5368e3b9890811f91784d3dbc1/coes-master-plan.pdf↩