Every few months, Artisans Asylum has a cruft swap. Cruft refers to the hypothetically useful things that our magpie-like tendencies cause us to accumulate. It’s different for everyone — some accumulate yarn or fabric samples. Others accumulate wholesale lots of obsolete industrial equipment. For someone with too much stuff, the cruft swap is both a blessing and an affliction; you come to give away something you finally convinced yourself to part with, but you leave with ten other somethings.

At the January cruft swap, there were old-timey snowshoes, broken laptops, and a milk crate full of rusty tools. I picked them up one after the other. I kept coming back to the axe. I put it down, thinking I would never need it. But its shape is so naturally suggestive of its function that simply picking it up seems to imbue the holder with magic lumberjack powers. Like suddenly growing fins out of your back would make you want to go for a swim. I picked it up again.

History

The origins of the axe were not hard to determine, since it was stamped with a logo and had a distinctive nail puller claw on the back. A search told me it was a “Tommy Axe” made by True Temper. Google Books shows that Popular Science and Popular Mechanics had ads for these axes in the 40s and 50s, so mine is probably from around that period. Here is an ad from the Popular Science April 1941 issue1, selling the axe for $1.50 ($23.70 in 2014 dollars2):

The history of the True Temper company is complex. The axe division originates with William Kelly, a metallurgist living in Kentucky in the mid-19th century. William Kelly was the American inventor of the Bessemer process for steel production, contemporaneously with Bessemer in England. This was the first method for mass-producing steel, reducing its cost by a factor of eight and making its widespread use practical for the first time. For whatever reason, Bessemer profited from his invention and Kelly did not, so he followed by his son, William C. Kelly, moved on to using their steel to make axes. They moved their operation from Louisville, KY to Alexandria, IN before settling in Charleston, WV in 1904. The reason for these moves was the search of a reliable supply of natural gas which was used as fuel for the factory. In the 1920s, they were the largest manufacturer of axes in the world3.

Kelly Axe Mfg. Co. was renamed to Kelly Axe & Tool Co. and merged with American Axe & Tool Co. in the 1920s. In 1930, they were purchased by American Fork & Hoe Co. which has an even longer and more convoluted history4. The True Temper name was used by American Fork & Hoe even before the merger. Some axes continued to carry the Kelly name for some time. In 1949, the company formally became known as True Temper along with all Kelly and American Fork & Hoe products, though even in the 1941 ad shown the old names are already nowhere to be found. The axe factory continued to operate in Charleston until 19825, when it was demolished and replaced by shopping malls. See here for maps and photos of the factory in its heyday.

The True Temper brand is now owned by the Ames Corporation and continues to produce tools in the USA. They have two large plants in Camp Hill, PA and in Carlisle, PA but details are scarce.

Cleaning

The first step after obtaining the axe was to remove the rust. This was easily accomplished by soaking it in a bath of vinegar. After a day, the rust came off easily with a brush, leaving a gray patina. One of the coolest things about this process was that the hardened ends of the axe turned a darker gray, with a sharp line marking them off from the softer middle part. This coloration disappeared in the sharpening process.

The handle has clearly seen better days, but it holds the head pretty firmly and I’m not ready to make a replacement, so I decided to leave it as is for now.

Here’s how the axe looked after I was finished scrubbing off the rust.

Sharpening

I looked at a variety of online guides to axe sharpening. The advice was broadly the same: use a file on the primary then the secondary bevel. The primary bevel on an axe is the overal wedge shape, which is what will split apart the wood when the axe is driven into it. But if it continued all the way to the end, it would result in a very thin edge which could easily be damaged by the high forces that an axe is subjected to. So the secondary bevel has a blunter angle to add strength to the edge.

A honing stone is then used to smooth the surface. I used an ordinary oilstone from the hardware store, first the coarse side and then the fine. It’s best to use a glove when doing this, because the hand passes quite close to the freshly sharpened edge. To ensure that the axe remains symmetrical, it is important to count the passes both with the file and the stone and make the same number on each side.

In the end, the axe was sharp enough to cut a piece of paper with little effort, which seems good enough to me. I know fancy sharpening experts can make an axe sharp enough to shave with, but that requires making a very fine edge which as mentioned above would reduce its usefulness for chopping wood.

The nail claw on the axe is an unusual feature and perhaps with good reason. To pull nails, the axe has to be held with the blade facing up, and any slippage of the claw could lead to accidental amputation. Nevertheless, I cleaned up the claw to maybe make it better at getting under nail heads:

Leather Sheath

About a year ago, I had taken a leather carving class at the Asylum. We each got a Basic Leathercraft Set from Tandy Leather and went through the instructions. I had been waiting for an opportunity to do it again, and here it was. I ordered a Veg Belly from Tandy to use as the leather.

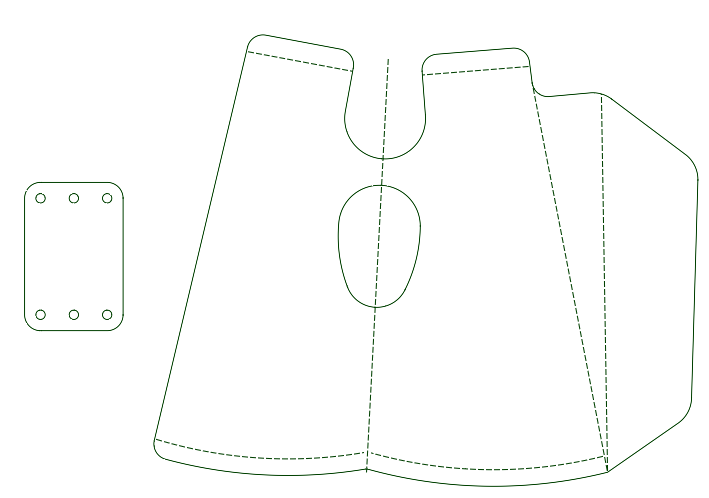

First I traced the outline of the axe head onto a sheet of paper, then made allowances for the sides. I ended up with this pattern, which I drew by hand but traced with a computer for this post. The rectangle on the left is for the belt clip.

Tommy Axe sheath template

I then traced it onto the leather, and fitted it onto the axe. After it had a bit of time to adjust to the new shape, I secured it with two-part rivets, and added the snaps. It would have been better to carve the logo and finish the leather before assembly, but I wasn’t sure at first if it would all fit together.

I traced the True Temper logo from the screen onto a piece of wax paper, and after doing a test, imprinted it into the final product. It’s a little wobbly but sufficient for my purposes. The process of carving leather this way is quite simple: first the piece is dampened and allowed to absorb the water. Then, the pattern is traced onto the leather through the wax paper with a pencil – because it is damp, it retains the marks. A special knife, included in the set, is used to score along the lines, and the background is hammered down with a metal tool. I used the dye included in the set to emphasize the background, and stain to give the leather its brown color.

-

According to this, issues of Popular Science prior to 1964 are in the public domain.↩

-

According to MeasuringWorth.com.↩

-

According to wvencyclopedia.org. ↩

) Tommy Axe Ad from Popular Science April 1941. ([*Source*](http://books.google.com/books?id=iycDAAAAMBAJ))](/images/2014/05/01/TommyAxeAd.jpg)