One Kendall Square in Cambridge, MA is a business complex with a variety of biotech startups, restaurants, bars, and a movie theater. Parts of it have been renovated or rebuilt in the style of modern office buildings, but some retain the 19th century brick facades typical of American mills and factories of that era. Since I often frequent Cambridge Brewing Company and other establishments, I became interested in the history of these buildings. They were built by the Boston Woven Hose & Rubber company and operated as a rubber goods factory from 1884 until 1981.

While I haven’t discovered anything in my research that would surprise anybody, I wanted to gather everything I found in one place for anyone else who is interested.

Rubber Manufacturing

The Americas were the first major source of rubber available to Western civilization. Natural rubber is made from the latex fluid produced by many plants, but most notably the Para tree of South America. Boston, as a major trading center, was a natural place for the rubber trade, as well as its industrial applications.

But rubber in its natural state gets sticky in hot weather and hard in the cold. This makes it unsuitable for manufactured products. The remedy to this was discovered in the mid-19th century, most famously by Charles Goodyear after whom the Goodyear tire company was posthumously named. With this new process called vulcanization, long-lasting rubber products like tires and hose could be produced. Many of the major milestones in the development of such products took place in New England. Goodyear himself operated a small factory in Springfield, MA.

Another important businessman was Nathaniel Hayward, who worked with Goodyear and produced rubber clothing in a factory village called Haywardville in what is now the Middlesex Fells. That factory operated until the 1890s.

More significant was the Boston Belting Co. which operated out of Roxbury. This company had its beginnings in the 1820s, prior to the discovery of vulcanization. They also crossed paths with Goodyear and went on to use his discovery to become a major manufacturer of rubber belts and hose which operated until 1926.

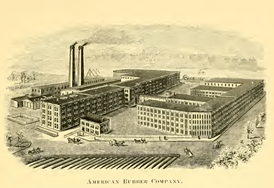

Right across the tracks from Boston Woven Hose in Cambridge was American Rubber Co., which was at one time the largest producer of rubber clothing in the world1.

Sadly, none of the above factories exist today. The Boston Woven Hose buildings are the only monuments I know of in New England to the pioneers of this technology. While rubber goods continue to be produced all around the world, these businesses were the beginning of the many rubber products that today we take for granted.

Cambridgeport and Broad Canal

First, a bit about where the factory was built.

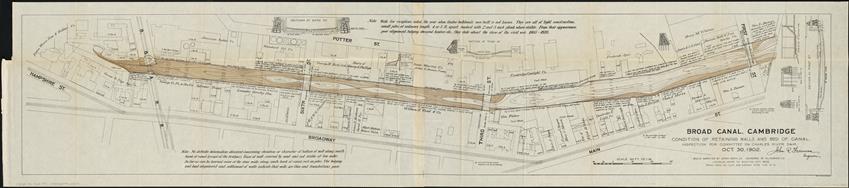

The City of Cambridge dates back to the earliest European colonies. But for centuries, the eastern part, adjoining the mouth of the Charles River, was a swampy estuary. In the late 18th century, canals started to be built to transport goods by water to inland towns. The Middlesex Canal, the Erie Canal, and dozens of others were built in this time period. Cambridge wanted to get in on some of this action and in 1805 was officially declared a port of entry by an act of Congress – hence the name “Cambridgeport.” At this time, the Charles River was not dammed, and was in theory navigable all the way from Boston Harbor. Broad Canal was dredged from the riverbank to what is now the corner of Hampshire and Portland Streets. Also built was Lechmere Canal further downstream. But as a consequence of decreased shipping during the war of 1812 and the relative convenience of Boston’s wharves, the project of turning Cambridge into a seaport never took off. Railroads began to be built in the 1830s, and the age of canals was over.

The Boston Woven Hose company was built on the corner of Hampshire and Portland in the 1880s. They and other companies along Broad Canal used it for transport of supplies and fuel. For some time, the Boston Woven Hose power plant got its coal deliveries this way as well. Increasingly, supplies began to be brought by railroad, and the only remaining use of the canal was to supply water for the plant’s operations.

I searched for any information about Broad Canal and found that most of the newspaper reports were mundane, reporting on drownings or accidents in the canal. However one interesting revelation was that the end of the canal was used as a swimming hole by local boys. An article in the Boston Globe from August 28, 1930 vividly describes an encounter between the boys and the police:

|

A group of Cambridge boys swimming in Broad Canal yesterday afternoon, clad only in nature’s garb, were suddenly interrupted in their sport by a squad of police in a patrol wagon. Twelve of the lads were caught by the bluecoats and taken to the Central Sq. Police Station for disturbing the peace after the boys, without a stitch of clothing, and the officers had an exciting time. The swimmers dived and swam under water and tried to elude the policemen. Shouts of the boys brought many motorists on Broadway to a halt. Two lads tried a movie-thriller escape by swimming down the canal toward the Charles River. As they stroked through the water several policemen ran after them along the bank. The running bluecoats proved too fast for the swimming youngsters and they were headed off at the 3rd St. Bridge and taken into custody. |

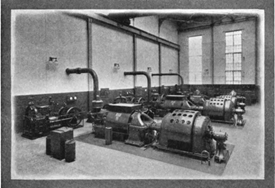

The problem is written about again on August 2, 1934. Apparently, numerous windows at American Rubber had been broken, and the youngsters were blamed. Police raided the swimming hole in a boat. Incidentally, the railroad bridge over the canal, visible in the power station photo below, was popularly known as “Dizzy Bridge” according to the article. The article goes on to state that “The boys were in varying moods while in custody. One entertained the others with a number of ballads given in a rich tenor voice. Three others were crying.”

On June 13, 1935, there was another raid, after “more than 100” windows were broken at the factories.

The thing that finally did Broad Canal in was the Kendall Sq. redevelopment of the 1960s. Many of the old factories including American Rubber were torn down, Broad Canal was filled up to its present length, and the NASA research center (now the Volpe transportation building) built on top. For more on the redevelopment, there is an article here with some great archival photos of Broad Canal and Kendall Sq. Here is another blog post talking about the redevelopment.

Now the future of the Volpe building is in doubt, and the possibility of uncovering Broad Canal again is being discussed (See the Connect Kendall Square Competition). I hope this idea comes to pass.

The Boston Woven Hose Company and its Products

Early beginnings

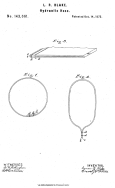

All the histories of Boston Woven Hose begin with Lyman Reed Blake, who is famous for inventing a leather sewing machine for attaching the soles of shoes just before the start of the Civil War. Gordon McKay, manager of the Lawrence Machine Shop, came upon his invention and became fabulously wealthy by supplying the Union army with footwear.

Blake went on to develop a machine which could analogously stitch tightly-woven cotton canvas or duck fabric into a tube. This machine led to the formation of the Blake Hose Company in 1870 which was not successful. It is said that the public was suspicious of hose which had a seam in it, and sales were slow.

Blake was financially successful from his shoe invention, but died at the age of 48 from tuberculosis.

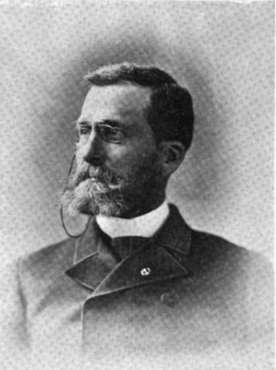

Theodore Ayrault Dodge

Col. Theodore A. Dodge was a decorated Civil War veteran, having lost his leg in the Battle of Gettysburg, and upon returning home became a businessman and war historian. His books on Alexander the Great and Hannibal remain popular on Amazon to this day. But it was while he was treasurer at the McKay Sewing Machine company that he formed the connections that bring him into our story2.

The sources are hazy on whether Dodge was part of the Blake Hose venture or whether he came in after its failure. In any case, in 1872 inventor James E. Gilliespie approached him with a machine that could weave seamless hose. Although seamless goods such as stockings were already being made by machine, a seamless fabric with the required tightness for making waterproof hose had not yet been mastered.

As explained in Gillespie’s patent 163925, “In this class of looms, as heretofore constructed, it has been impossible to weave tubular fabric of sufficient strength, or with warp and weft sufficiently compacted and accumulated, to form practical hose for hydraulic purposes, because the warp-carriers, as heretofore constructed, could not be brought sufficiently close together […].” It was this deficiency that his new machine tried to rectify. However, it was overly complex and unreliable, supposedly containing 80,000 parts.

Nevertheless, Dodge persevered, and with the assistance of inventor Robert Cowen they continued developing the product, spending (according to Dodge) the scarcely believable sum of $150,000 ($3.5 million today) on their research. In 1880, they began producing hose in two rented rooms of the Curtis Davis Soap Factory on Portland St. Initially, their product was just seamless cotton tubing, to be rubberized elsewhere.

I have not been able to find a patent for a redesigned weaving loom. It’s possible that Cowen concluded that a special loom was unnecessary, given a satisfactory rubber lining. In 1880 patent 226038 for weaving fabric hose around a rubber tube, “I desire it to be understood that I make no specific claim for the apparatus herein shown for making the textile part of the hose, as it is well known and in common use, and instead of the apparatus shown I may employ any other well – known equivalent apparatus to either weave, braid, or knit the textile covering.”

In 1884, the company outgrew its accomodations, and put up the first buildings on the corner of Hampshire and Portland. Dodge remained in control of the company until a reorganization in 1898 led to his retirement, and he continued writing his war histories and vacationing in Paris until his death in 1909. He married twice, and had three surviving children. He is buried at Arlington Cemetery.

Robert Cowen

Cowen was apprenticed to a machinist in Worcester at the age of 12 as he “early evinced a decided bent for machines.”3 He was only 23 years old at the time he joined Dodge in his venture, and quickly became the mechanical mastermind of the Woven Hose factory. He soon became vice president of the company, an office he held until the reorganization when he was made technical manager of the plant.

He died in 1902 at the age of 53 as a consequence of what the newspaper calls “ulceration of the stomach.”4 It is said that he was much loved by his employees, and a crowd of 600 attended his funeral5.

He married twice: his first wife, Emma Thomas, died in 1884. He had one child with her. He had three children with his second wife, Emma J. Rawson. Incidentally, she was the daughter of another prominent Cambridge machinist, George W. Rawson. His firm Rawson & Morrison, just a few blocks down Broad Canal, produced steam engines and hoisting machinery.

Further History

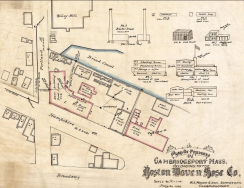

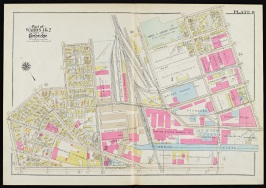

The first brick building, right on the corner, was built in 1884. Luckily the plan of the site as built is readily available.

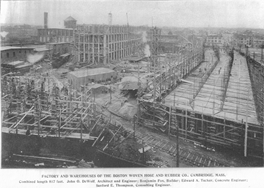

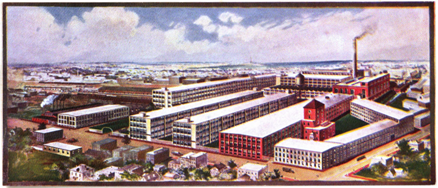

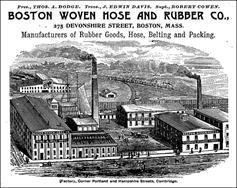

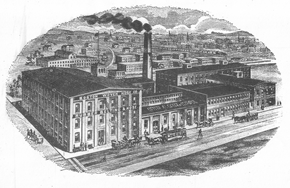

An engraving of the factory from the 1880s. |

Cambridge Tribune Article (Click to view full size) |

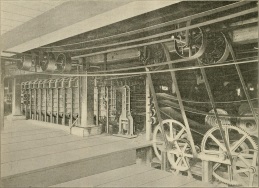

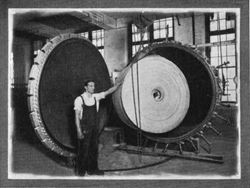

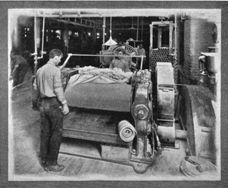

On March 31, 1888, the Cambridge Tribune published a full-page article detailing the Boston Woven Hose factory, with many photographs of the interior. The factory employed 200 at this time. Here we learn some details such as that a 340 HP steam engine powered the factory.

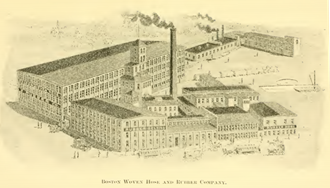

A second engraving of the factory, from Cambridgeport: Its Representative Businessmen, 1892.

(Source: Cambridge Historical Commission).

The second brick building visible from Hampshire St. was built in 1892.

Another engraving of the factory, from The Cambridge of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Six. Note addition of the larger brick building.

In 1896, Cambridge published the book The Cambridge of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Six to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of being incorporated as a city. Theodore A. Dodge took a break from his war histories to write a four page retrospective of the company. Several of the factory building engravings on this page are from this book. By this time he writes that he had distanced himself from plant operations, and retained only an advisory role. As of 1896, the company employed 975.

In the 1890s, bicycle tires were first developed, and the company came out with their own brand, called Vim tires. In 1898, business slowed, but the company did not slow production in time and as a result ended up with a large stock of tires they could not get rid of. Rubber in those days was not as stable and didn’t have a long shelf life. The company nearly went bankrupt. This is what prompted the reorganization which caused Dodge and Cowen to lose their executive positions. It seems that the company stopped making bicycle tires after this point.

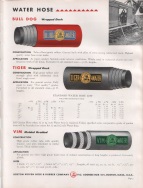

Aside from bicycle tires and hose, the company made a number of other rubber products such as rubber rings for canning jars, flat belting for machinery, heels and soles of shoes, and other rubber goods.

According to this, the town of Franklin, NH purchased a complete fire hose wagon from BWH in 1895 for $310.00. Presumably they did not build wagons themselves, but furnished them as part of a package.

In 1906, the company expanded onto the site of the Chelmsford Foundry next door along Portland St. (now Cardinal Medeiros Ave). Between 1907 and 1916 they erected the group of long concrete buildings which make up most of the company’s footprint.

The power plant was built in 1912 by Stone & Webster. It had a capacity of 3250 kW6, an 11-fold increase over the old steam engine. It was abandoned in 1946, presumably the factory started using city power. It was razed in 1999.

A brass foundry was constructed in 1907. Here they made brass nozzles and other fittings that go naturally with garden and fire hose.

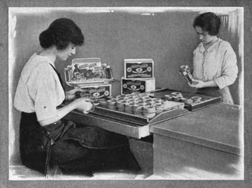

In 1916, the company published a short book entitled The Story of Rubber, What It Is And What It Does describing the history of rubber production, and the company’s products. Many of the illustrations on this page are taken from there.

In 1928, the Page Box Company property next door on Hampshire St. was purchased, and Boston Woven Hose buildings erected there in 1952. At its height, BWH had around 1600 employees and occupied two large city blocks.

A 1934 catalog shows a variety of industrial belt and hose applications.

Although the buildings were top-of-the-line when they were first built, by the 1950s, they were outmoded. The long, narrow, multistory factories of the 19th century were designed to let in the maximum amount of natural light, so that every worker could be working near a window. By the mid-20th century, artificial lighting had obsoleted this requirement, and the need to transport goods between floors became an unacceptable bottleneck. Thus the company began losing to more modern concerns. The company was taken over by American Biltrite Co in 1957. This was also the year that the brass foundry stopped operating.

In 1964, a retrospective entitled “Boston Woven Hose and Rubber Company: Eighty-Four Years in Cambridge” was published by the Cambridge Historical Society. This contains much of the information cited on this page.

American Biltrite finally ceased operations at this location in 1981, ending close to a century of rubber manufacture 7. The inefficiency of the buildings was again cited as a cause.

The Vim Tricycle

One of the more outlandish products of Boston Woven Hose was this enormous tricycle, built around 1895. The tricycle demonstrated the company’s prowess in tiremaking, and I suppose it was a sort of predecessor to the Goodyear Blimp as far as rubber company promotional stunts go. The trike participated in a number of parades. In December 1896 it was even taken to England8 and returned in May 18979.

In 1899, a brochure entitled “Remarkable Cycles” by Harold J Shepstone described the visit:

Brass nozzle

As mentioned, one of BWH’s products were brass nozzles for hose and other accessories. It is still not too difficult to find some of these on eBay. I had the idea of taking a nozzle and bringing it back to its birthplace. I got a handsome specimen and polished it with Noxon, sealing it with brass instrument laquer to preserve the shine. I also added a wooden insert for the nozzle to rest on.

I took it to Cambridge Brewing Company and presented it to the owner. It now resides on the shelf behind the bar as a reminder of the building’s history.

-

The New England States: their constitutional, judicial, educational, commercial, professional and industrial history, Volume 1, William Thomas Davis, 1897. p. 356.↩

-

An inscription attached to the photo above reads, “Capacity: 3250 Kw. Installed. Power House: Brick with steel frame, supported on pile and concrete foundations. Boiler room, 50’ x 120’; Turbine room, 101’ x 50’. Chimney: 11’6” x 167’, radial brick. Crane: 20 ton, 1 motor. Coal Handling: Coal is elevated to power station bunkers by bucket elevator and belt conveying equipment. Circulating pumps: One 8” and two 10” centrifugal circulating pumps, direct connected to a 60 HP and 70 HP non-condensing steam turbine. Water is taken from Broad Canal.”↩